I pray for blood: the split narrative of life with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

23rd April 2021 by Jesse King

April is Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) Awareness Month. Jesse King shares their experience of misdiagnosis, mistreatment and the medical model.

I just thought there were two of me.

One that I liked, and one that I had to monitor closely like a misbehaving child, constantly picking up the pieces and apologising for. The first Jesse is an eccentric, comical, observational, energetic go-getter. The second Jesse is the opposite – a second-guessing, self-deprecating, suicidal, chronically anxious, and sleep-deprived angry weeping ball of their other self who can only see through the lens of perceived rejection.

After many years of dipping in and out of psychiatric services with no result, living in a state of missed or borderline diagnoses, I finally found a correlation that brought the first shred of certainty to my chronically uncertain and chaotic life. I didn’t think the answer would be between my legs.

Jesse 1 is the only Jesse I knew until I was twelve years old. Then along came my first period, accompanied unbeknown to me at the time, with a new alter ego called Devastation. Back then, this was attributed to teenage-hood. Over 17 years later, however, I don’t think I can pass this off as teenage angst, despite my baby face.

It turns out I wasn’t as alone as I thought I was. Despite this chronically medically under-researched* condition of people-who-menstruate (*ah, that explains it! The medical model of disability’s gender bias strikes again!) persuading me for years that it was simply just me. And despite mental health professionals trying to diagnose me with Bipolar II and then Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder, both of which did not feel correct due to the cyclical nature.

Discovering PMDD

Then, one day at the gym I heard on a podcast, the acronym that would bring sense to the first 28 years of my life.

PMDD is a hormone-instigated, cyclical, mood disorder that affects how a menstruating individual responds, in both thoughts and behaviours, to menstrual hormones. It most often starts around ovulation (the luteal phase) to a few days into the start of the period. We’re looking at about 10-14 days of changes in mood, thoughts, and behaviours-sometimes a lot more if you have irregular periods like me. That’s half of the month spent in emotional and physical pain. That’s half of every month, for the rest of my life, spent waiting desperately for my period to come as I sit in a pool of anxiety, depression and distress.

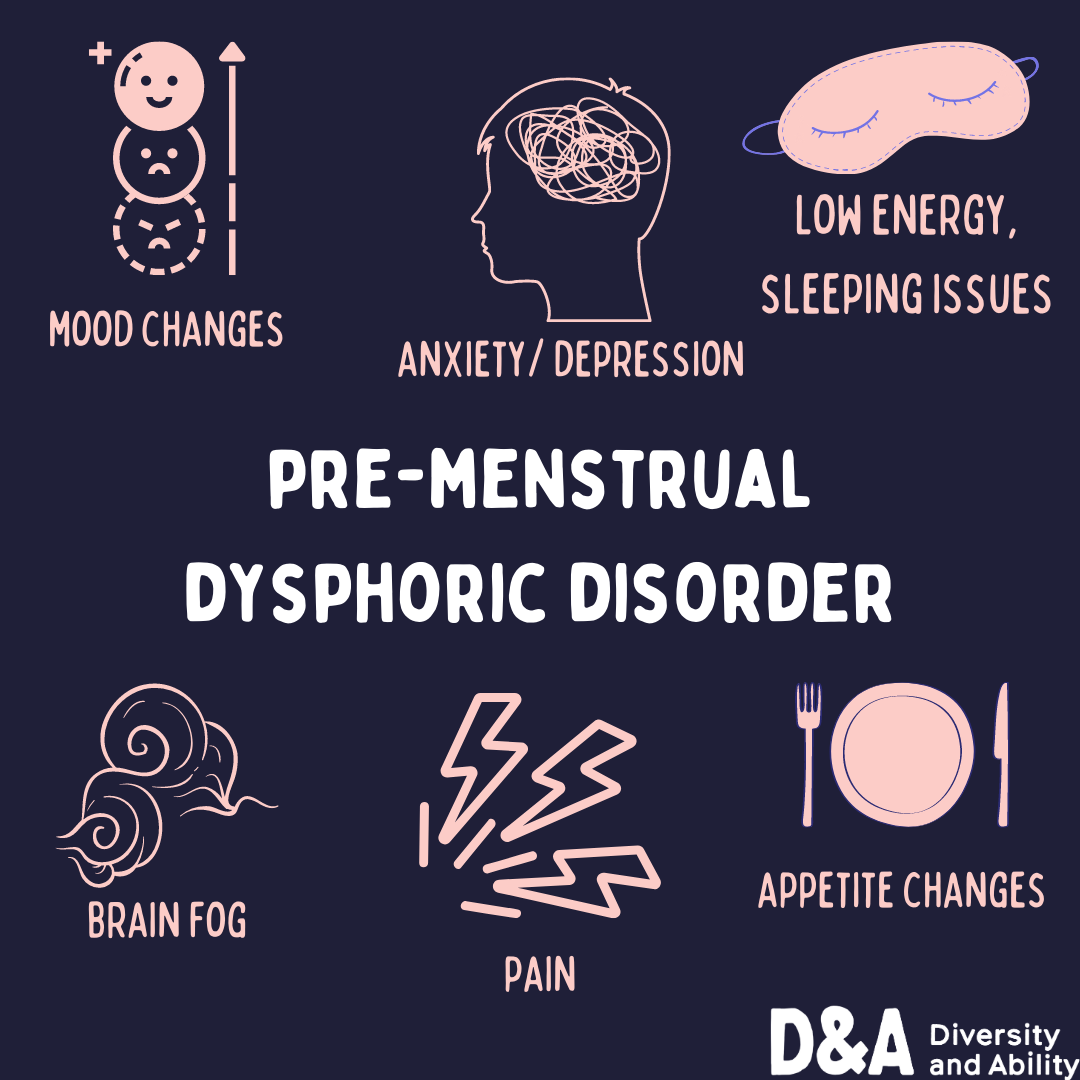

The International Association For Premenstrual Disorders (IAPMD) notes the symptoms of PMDD as:

- “Mood/emotional changes (e.g. mood swings, feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection)

- Irritability, anger, or increased interpersonal conflict

- Depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, feeling worthless or guilty

- Anxiety, tension, or feelings of being keyed up or on edge

- Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g., work, school, friends, hobbies)

- Difficulty concentrating, focusing, or thinking; brain fog

- Tiredness or low-energy

- Changes in appetite, food cravings, overeating, or binge eating

- Hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness) or insomnia (trouble falling or staying asleep)

- Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

- Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, bloating or weight gain”

Wait..

Does this mean the anger, the self-hatred, the exhaustion and fatigue, the howling for hours on the floor, in complete emotional and alarming distress, until the salt sticks the side of my face to the carpet, aren’t just parts of my constitution that are inherently wrong and bad?

I was then able to connect the dots retrospectively and see a pattern. All of the two weeks that have felt like 100 week waits throughout my life, as I cry for hours for no reason, were a reaction and sensitivity to my body’s normal monthly hormonal changes. To have a reason, finally, was incredibly validating.

‘One big apology’; returning to ‘normal’ life

When raised estrogen drops, the blood comes. I can now enter the “clean up” stage, as I frantically scramble to repair the devastation I’ve caused, to try and carry on with every aspect of my life that I have put on hold for the last two weeks, before those same two weeks are my reality again and I am stuck. This is technically the “relief” phase, where symptoms are lifted and ‘normal’ life regains. However, the residing shame, guilt, regret, and the mammoth list of apologies or anxious attempts to re-spark friendships where I’ve let the tea go cold from not replying to attempts of communication, ever, mean that relief becomes one big apology.

For me, the most devastating consequence of my PMDD has been its effect on relationships around me. Vicious Cycle PMDD report that, “About half of individuals with PMDD report losing an intimate partner relationship due to PMDD”. Rejection sensitivity or an increased belief of rejection is a painful, exhausting and terrifying state to be in. In this state, for example, even a small change in a partner’s tone can result in feelings of assumed forecasted abandonment, in my experience, this does not make for happy families.

Attempting diagnosis

Although it was easy to self diagnose my PMDD, it was not an easy matter getting myself an ‘official’ diagnosis. When I approached my NHS mental health service, after waiting twelve months for an initial appointment, I was met by blank stares from the Primary Care Mental Health Practitioner and a “what’s that?”, which is not a welcome experience for an individual putting their trust and hope into receiving support and care.Trying to educate a white male medical professional is possibly the most difficult task I have ever had to repeatedly endure. And often it leaves you back where you started, a little bit more distressed, a little bit more alone, a little bit more marginalised.

Vicious Cycle PMDD is a worldwide patient-led PMDD awareness collective started by Laura Murphy (who was a guest speaker in that infamous podcast in the gym) in 2017, which aims to unite lone PMDD sufferers throughout the world and help spread education and understanding of “this poorly understood condition” to the general public and healthcare professionals. If it wasn’t for finding various patient-led online platforms, such as Vicious Cycle and IAPMD,

I wouldn’t have had the confidence to advocate for myself by going to my GP and demanding that they listen to me, that this condition exists and is real, and presenting them with a wealth of resources and information as armour.

Unfortunately, as PMDD is under researched and very poorly understood, there is currently no known cure or treatment plan, and limited understanding of why it occurs in the first place, despite it affecting 5.5% of all menstruating humans. With the growing advocacy, awareness and social media coverage, there are now more and more of us being diagnosed worldwide, and I hope it can begin to be caught and identified earlier than it was for me, so less time is spent in doubt, shame and pain.

What’s next?

You can learn more about PMDD through Vicious Cycle, IAPMD or Mind. If you think you may have PMDD, they also have a range of resources to help educate your GP and others around you, should you need them.

If you have PMDD and are working or in education, you could be entitled to support that would help remove some of the access barriers you face. Find out more about Disabled Students Allowance (for those in education) or Access to Work (for those in the workplace).